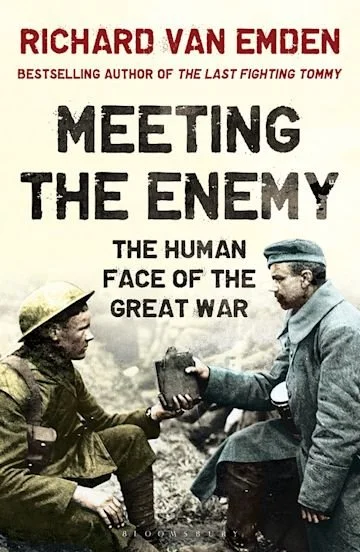

Book Review - 'Meeting The Enemy: The Human Face Of The Great War' by Richard van Emden

‘The First World War conjures harrowing scenes of shattered trees, barbed wire wastelands and colossal loss of life. While this is one part of the story, it is far from the complete picture. Meeting the Enemy unearths the incredible stories of what happened when British and German troops and civilians interacted on the Western and Home Fronts between 1914 and 1918.

From the first British casualty of the war and the famous Christmas truce to stories of enemies going to extraordinary lengths to make sure families of fallen or captured soldiers knew their fates. Leading First World War historian Richard van Emden explores both the horrendous brutality and the great humanity of those who found themselves caught up in the conflict. With extracts from unpublished diaries and letters and a wealth of original photographs, Meeting the Enemy shows the human face of the Great War as never before.’

In the introduction to this book, published in 2013, van Emden writes: ‘Social, cultural and military ties between Britain and Germany were particularly strong before the outbreak of war. Germans made up the third largest immigrant population in Britain prior to 1914 (behind Russian Jews and the Irish); they set up businesses, commercial and industrial; Germans constituted… the largest group of foreign students… in London’s upmarket hotels and restaurants young Germans were conspicuous by their presence, working front of house (10 per cent of London’s waiting staff were German). They intermarried, settled and had families. Elsewhere, German academics, musicians and writers featured large in pre-war musical and literary circles…

‘… Kaiser Wilhelm was Colonel-in-Chief of a British regiment, the 1st (Royal) Dragoons… each year the Kaiser sent a laurel wreath to ‘his’ regiment in commemoration of the Battle of Waterloo…’

Despite these friendly ties, in the years leading up to the outbreak of war, Germany’s ship-building endeavours propelled it to second place behind Britain in the arena of maritime supremacy and was ultimately seen as posing a threat to Britain.

Instead of focussing solely on the direct contact between the forces of these 2 nations, van Emden has also included the no-less important contact of soldiers with civilians and civilians with civilians.

He’s used a chronological framework, moving ‘back and forth from the Western Front to the Home Front…’, including the contents of ‘many unpublished letters and diaries… [and] government documents…’

One of the first things the British government did following their entry into the war was to pass the broad-sweeping Defence of the Realm Act to ensure Britian’s safety, which gave the ‘government wide-ranging powers over public and press, with rights to requisition property and land and to control the transport network… Individuals contravening the Act were liable to court martial with fines, imprisonment and… death…’

The one topic in this book that totally surprised me was the treatment of British women who married German or Austrian men.

Those who married a foreign national were legally ‘deemed by… the Naturalisation Act of 1870 to have automatically adopted her husband’s nationality…’; even when their situation changed, either through the death of the husband or through separation/divorce, they remained an alien subject.

If the German man decided to apply for and was granted British citizenship, ‘then his British-born ‘German’ wife would be issued with a certificate of naturalisation to confirm her new legal status – as a Briton.’

To me, this seems unfair, but Britain was actually bringing its law into line with the legal position in Europe, including France and Germany.

Many of these women were shocked to find themselves on the wrong side of the law because they, obviously, still believed themselves to be Britons, and didn’t realise that the Aliens Restriction Act also required them to register with the police as they were deemed enemy aliens.

Similar impositions were applied to the German-born wives of British men living in Germany.

van Emden covers, in fascinating detail, the Christmas Truce of 1914, using personal letters of the soldiers who were part of it.

As expected, both sides were reluctant to return to actual fighting; ‘in some places the truce lasted several days…’ with the 1/6th Gordon Highlanders stretching it out to the 3rd of January 1915.

During Christmas Day, the Scotsmen discovered that many in the German ranks had lived in Britain prior to the war, returning to Germany to enlist.

On the 3rd of January, ‘a German officer, with an interpreter… met a captain of the Gordon Highlanders… [and informed] the captain that instructions had been received… that the war must be resumed… it was agreed the truce would end in one hour…’

Not only did news of the Christmas Truce spread quickly among soldiers in other areas, it wasn’t long before the British public also learned of it from family members serving at the front, and the inevitable reports in the press.

Images of ‘smiling British and German soldiers at ease with one another…’ were printed in newspapers, along with letters written by soldiers; letters which included lines like, ‘“I have now a very different opinion of the German…”’

It’s not difficult to imagine the furious reaction of the military top brass.

This led to private cameras being banned at the front, stricter censorship of letters, and orders being given to ensure nothing like the Christmas Truce was ever to be repeated, and ‘no further fraternisation with the enemy would be tolerated.’

However, another truce did occur again in December 1915, albeit on a smaller scale, and van Emden also covers this with more letters from the soldiers who experienced it.

Most articles and books on the First World War tend to focus on the horrible suffering and unremitting death in a nightmare landscape.

Yet there was also humour, ‘albeit much of it black… passive, easy-going relations with the enemy and… the German-baiting fun that saved morale…’

During the day, when attacks were less frequent, and routine monotony was commonplace, ‘shouted conversations with the enemy were heard and might begin with a simple “Morning, Fritz” and other pleasantries, or with bullish insults, depending on the mood.’

Yet another thing I learned – one of many things – while reading this book was the question of what to do with ‘males born in Britain to enemy subjects.’

Allowing them to enlist was out of the question, so, in 1916, the Army Council authorised the creation of a couple of new battalions.

These trained, unarmed men were sent to Infantry Labour Companies ‘that would work behind the lines in 1917 and 1918.’

These men were not totally trusted, and most of the work they carried out, although repetitive, was physically demanding.

van Emden hasn’t ignored those whose battlefield was the sky, and reading pilots’ letters describing their ariel combat heightened my admiration and respect for them.

There appeared to be no animosity between pilots of either side when they came face-to-face with one another.

Their interactions were polite, with some even offering to drop notes behind enemy lines confirming the captured pilot was alive and whether he’d been injured.

The most harrowing account in this book, in my opinion, is the forgotten story of the British prisoners of war who’d been sent to the Eastern Front, purely, it would appear, as reprisal.

Both, the British and the Germans, automatically distrusted each other’s assurances about the treatment of prisoners of war.

When Britain agreed to ‘lend the French 2000 German prisoners of war for work in… Rouen and at the docks at Le Havre’, located 60 and 100 miles respectively from the Somme, a furious Germany reacted by sending 2000 British prisoners of war from Germany to the Eastern Front.

The prisoners who bore the brunt of this reprisal were 500 ‘regular soldiers or Royal Naval Volunteer Reservists… from the Royal Naval Division… captured either during or shortly after the retreat from Mons or at Antwerp, where [they’d] landed in… September 1914… These men were… despised by the Germans… [they’d] frustrated… [the] thrust towards Paris and ultimately cost Germany the quick victory promised to the nation.’

These hapless men were ‘sent to the trenches between Riga and Mitau… within range of Russian artillery fire… in temperatures as low as -35°C and forced to work with little or no food, returning to a camp and… tent pitched on a “frozen swamp.”’

Many died; those who survived lost ‘toes, fingers, hands and feet, through severe frostbite and amputation.’

Despite the horrors, van Emden has also detailed the compassion shown to those regarded as enemies.

We learn of this through letters sent by German soldiers to the families of British soldiers who’d been injured and captured.

The German soldiers wrote of how they’d come across the injured soldiers and helped them, after which the British soldiers had asked them to write to their families to inform them of their fate.

At least one resulted in a strong bond of friendship.

In Cambrai in northern France, the Germans had established the Cambrai East Military Cemetery ‘for war dead irrespective of nationality. It was designed with great care and attention, and included monuments to German, French, British and Empire dead and in the centre a memorial stone with the words inscribed: “The Sword divides, but the cross unites”.’

The details van Emden has included leading to the end of the war, and the state of Germany especially, and Britain immediately afterwards gives a much fuller, more complete picture of the First World War because we see things through the eyes of the people who lived through it.

This is the first book I’ve read by Richard van Emden, and it certainly won’t be the last.

His level of research is impressive, and he has an easy writing style.

By including so many letters and anecdotes of the soldiers and civilians who’d lived through that time, he’s made this one of the best books I’ve read in quite a while.

With most of First World War literature focussing on the battles and soldiers’ combat experiences, this book has given me a more complete picture of what the war was like, from beginning to end, not only from the civilians’ point-of-view but also the soldiers on the front line.