History - Japan In World War I

On board a Japanese destroyer at Marseilles with other destroyers in view (W.Commons)

The more I read about the First World War, the more I realise how much I don’t know.

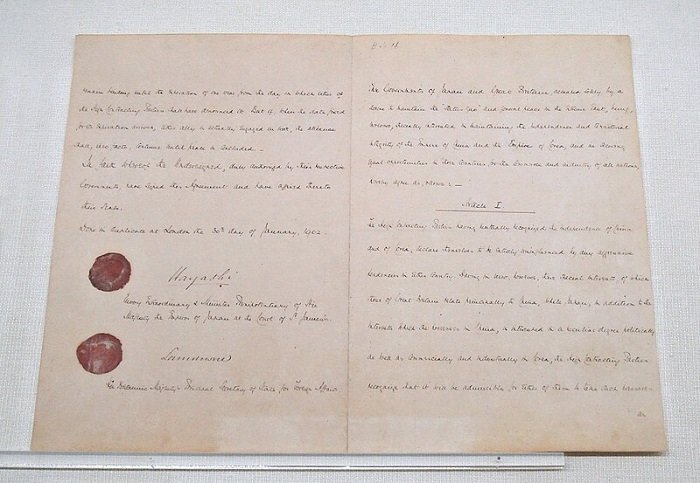

Case in point, while Britain and Japan were enemies during the Second World War, I was oblivious to the fact that they were allies in the lead-up to the First World War, having signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902.

Anglo-Japanese Alliance 1902 (World Imaging - W.Commons)

This alliance provided assurance that both countries would assist one another in defending their respective interests in China and Korea.

It was also seen as a means to stop Russia’s expansionist policy in the Far East.

At the start of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, which Japan won, the Anglo-Japanese Treaty deterred France, Russia’s ally, from entering the war.

The Alliance was renewed in 1905 and, again, in 1911.

At the start of the First World War, Japan declared war on Germany despite the misgivings of those in positions of power in the government and the army who believed Germany would win.

The war in Europe barely registered in the lives of the Japanese people and no troops were sent to the Western Front.

However, Japan played a major role in one battle in the Pacific theatre of war involving the capture of the German colony of Qingdao (Tsingtao) in China in 1914.

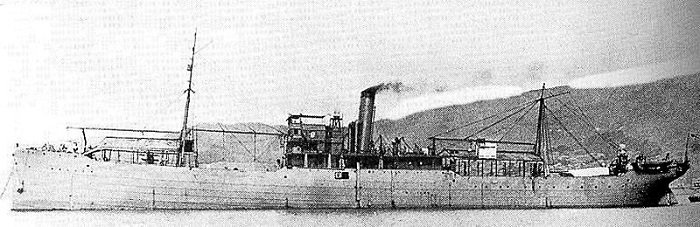

The fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy was strengthened with the Royal Navy’s HMS Triumph and the destroyer HMS Usk.

HMS Triumph 1903 (W.Commons)

HMS Usk (W.Commons)

The Japanese fleet included the seaplane carrier Wakamiya; its airplanes were the first of its kind to attack sea and land targets.

Japanese seaplane carrier Wakamiya (W.Commons)

These airplanes, Maurice Farman seaplanes, were also the first to take part in a night-time bombing raid.

Japanese Maurice Farman seaplane (W.Commons)

With the Allied blockade in place, Japanese troops began shelling the fort and the city on the 31st of October.

On the 7th of November, the fortress surrendered to the Japanese forces.

2nd Battalion The South Wales Borderers, along with a detachment of the 36th Sikhs, formed the bulk of the British troops sent to assist the Japanese in capturing Germany’s naval base at Tsingtao (Qingdao) in China. From an album compiled by Brig NW Barnardiston, commanding British troops in North China, 1914 (W.Commons)

After this, the Imperial Japanese Navy spent the war patrolling the South China Sea and Indian Ocean.

Until 1917.

In February of that year, German U-boats resumed their campaign to destroy all British vessels in the North Atlantic, and the Royal Navy was stretched thin with continuous patrols and escort duties.

Following repeated requests from Britain for assistance, Japan sent 8 destroyers and a flagship cruiser to assist the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, with the number of destroyers eventually totalling 14.

The Japanese force, based in Malta, was named the Second Special Squadron and its main mission was to escort British ships and protect them from German U-boats.

WW1-era photo from Malta's National War Museum shows Imperial Japanese Navy officers sitting at Marsa Race Court (W.Commons)

The First Special Squadron had been dispatched to help defend Australia and New Zealand, and Allied shipping in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

By the end of the war, the Second Special Squadron had taken part in over 340 escort missions including 34 combat operations and a rescue mission.

The rescue mission involved 2 of the Squadron’s Kaba-class destroyers, the Matsu, and the Sakaki, and the troop transport Transylvania.

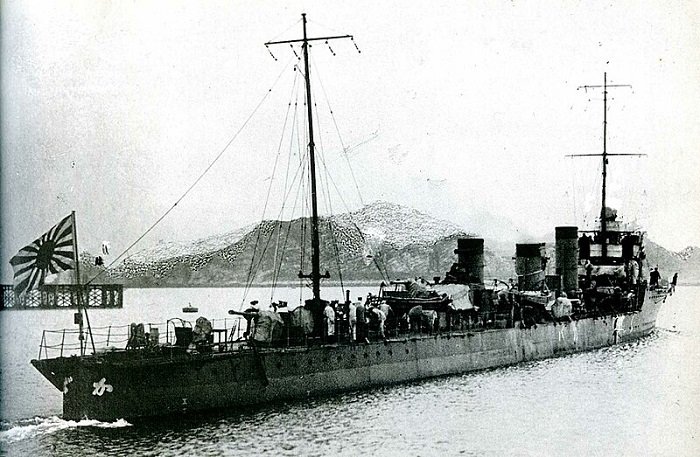

Destroyer Kaba (same class as Sakaki) 1925 (W.Commons)

Both destroyers were launched in 1915, and both patrolled the area around Singapore before being sent to the Mediterranean.

The Transylvania was completed just before the start of the First World War and was to have been part of a subsidiary of the Cunard Line but was taken over for service as troop transport.

On the 3rd of May 1917, the Transylvania left Marseilles bound for Alexandria in Egypt, escorted by the Matsu and the Sakaki.

On board were 2,860 British troops, 200 officers, and 60 Red Cross nurses.

On the morning of the 4th of May, not far from Savona in the Gulf of Genoa, a torpedo from the German submarine, U-63, struck the engine room of the Transylvania.

While the Matsu came alongside to take troops on board, the Sakaki circled, forcing the submarine to remain submerged.

After about 20 minutes, a second torpedo was seen heading towards the Matsu, which managed to take evasive action.

But the torpedo struck the already damaged Transylvania, causing it to rapidly sink, resulting in the deaths of 10 crew members, 29 officers, and 373 soldiers.

On the 11th of June 1917, while patrolling in the Aegean Sea between Greece and Crete, the Sakaki was torpedoed by the U-27, an Austro-Hungarian submarine.

Of the 92 crew, 68 were killed, including the captain, Commander Taichi Uehara.

Japanese sailors bring ashore boxes containing cremated remains of Sakaki’s crew (W.Commons)

Although the contribution of these Japanese sailors is barely remembered in Japan, there is a memorial at the Commonwealth War Graves in Malta, commemorating the Japanese sailors who lost their lives, including those from the Sakaki.

In researching the role of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Mediterranean, I came across this ‘Japan Times’ article which details a first-hand account of the sinking of the Sakaki and the courage of her crew – well worth a read.