History - Deokhye, The Last Princess of Korea

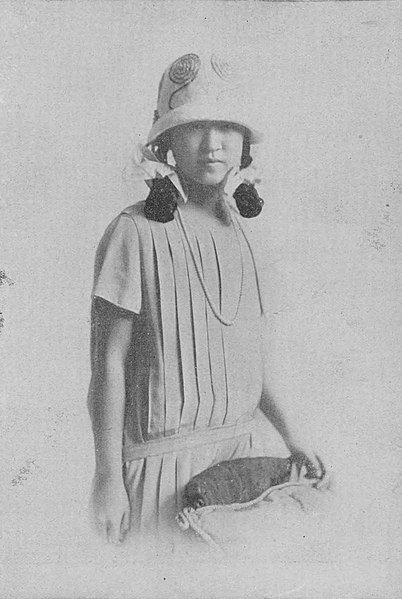

Princess Deokhye, around 1923 (Wikimedia Commons)

I’m not at all familiar with Korean history, something I wanted to rectify after watching the Korean medieval horror, ‘Kingdom’, set in the era of the Joseon dynasty.

While reading up on the history, I came across the last members of the Korean royal family, and the story of their last princess whose life was anything but charmed.

Princess Deokhye was born on the 25th of May 1912, at Changdeok Palace in Seoul.

Her father was the Emperor Gojong, and her mother, Yang Gwi-in, one of his concubines.

Emperor Gojong by Percival Lowell (1884) (Wikimedia Commons)

Princess Deokhye’s mother, Yang Gwi-in (Wikimedia Commons)

Gojong was the last king of the Joseon dynasty, which ruled over a united Korea from 1392 for more than 500 years.

His reign lasted from 1864 to 1897 after which he became the first Emperor of Korea until he was forced to abdicate in 1907.

While this post is about Princess Deokhye, I think it’s important to mention the events leading up to her birth as they played a huge part in shaping her life.

So, I’ll begin with how her father ascended to the throne.

In 1864, King Cheoljong, the 25th king of the Joseon, died without an heir, which left the selection of the next king in the hands of three dowagers, one of whom was his wife.

A member of the Andong Kim clan, his wife saw an opportunity to increase the power of her clan and claimed the right to choose the next king.

Traditionally, however, that right fell to the oldest dowager, Queen Sinjeong, who had been the wife of the 24th king who had also died childless (Cheoljong had been a distant relative of his).

Queen Sinjeong was of the Pungyang Jo clan, the only real rival to the Andong Kim clan.

As King Cheoljong grew increasingly ill, Queen Sinjeong was approached by a member of the Yi clan who had been a distant relative of the 16th Joseon king, and whose father, through adoption, had been related to the 21st king.

This obscure branch of the Yi clan had managed to survive various political intrigues by not forming any affiliation with any factions.

Himself ineligible for the throne, the man who’d gone to Queen Sinjeong believed his second son, 12-year-old Yi Myeong-bok, was a possible successor, and the dowager agreed.

On the 21st of January 1864, Yi Myeong-bok became King Gojong with Queen Sinjeong ruling in his stead as regent.

His father was granted the title Heungseon Daewongun, and Queen Sinjeong invited him to assist his son in ruling.

In 1866, Queen Sinjeong renounced her right to be regent, and although she remained regent, it was Gojong’s father, the Daewongun, who then became the true ruler.

During the Daewongun’s rule, France and America attempted to begin trading with Korea but were unsuccessful because of the king’s policy of isolationism against any Western power.

In November 1874, after Gojong began his direct rule and the Daewongun was forced into retirement, Gojong’s wife, Queen Min (posthumously known as Empress Myeongseong) and her clan gained total control over the court.

Unlike the queens who’d preceded her, Queen Min was more ambitious and assertive, and, about 5 years after her marriage, at the age of 20, had begun to play an active part in politics.

All through this time, Korea was still subordinate to the Qing Dynasty of China, but Japan had long sought to take control of Korea for themselves and make it a puppet state; Korea was literally ‘piggy in the middle’ between China and Japan.

Tsushima Island, located between Japan and Korea (wikimedia commons)

Japan had already utilised the assistance of the Sō family of Tsushima, an island situated between the Tsushima Strait and Korea Strait about halfway between Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula, to play the role of intermediary in Japanese-Korean relations, and they had done so successfully for centuries.

The Sō clan had ruled Tsushima from the late 16th century until the reorganisation of Japan’s society in the 1860s and 1870s and would eventually come to play a big role in the life of Princess Deokhye.

During the period of political instability in Korea following Gojong’s rise to power, the Meiji Restoration in Japan was leading to big changes for that country as it rapidly industrialised and adopted Western ideas.

1894 saw the start of the First Sino-Japanese War as Qing China and Japan fought for influence over Korea, with much of the war being fought in Korea.

Japan’s superior military technology brought them victory and in February 1895, Qing China sued for peace.

In 1876, Japan forced Korea to sign the Treaty of Ganghwa, an unequal treaty, which would allow Japan to enter Korean territory for fish, iron ore, and other natural resources while also allowing Japan to establish a strong economic presence there.

The Treaty also gave Japanese citizens extraterritorial rights in Korea, meaning they would be exempt from the jurisdiction of local law.

It’s no surprise then that Gojong had no love for the Japanese Empire.

Queen Min’s ever-growing involvement in politics led to her looking to outside support, including China and Western powers, to keep Japan in check.

But this earned her the enmity, not only of Japan, but many traditionally minded aristocrats.

In 1895, the 43-year-old Queen Min was assassinated by Japanese agents aided by Koreans loyal to her father-in-law who despised her.

According to Peter Duus, a historian of Japan, the assassination was a “hideous event, crudely conceived and brutally executed.” (‘The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895-1910’)

Gojong’s hatred towards Japan only deepened after this and, in 1897, he declared Korea an empire and began the Gwangmu Reform, which encompassed the military, the economy and education with the aim of modernising Korea.

Gojong was subjected to several assassination and abdication attempts.

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, which Japan won, diplomatic efforts to keep Korea independent failed.

When Japan learned of these efforts by Gojong, they eventually forced him to abdicate in 1907, and he was succeeded by his son, Emperor Sunjong.

Gojong and his retinue were confined to Deoksu Palace where he made numerous attempts to seek refuge outside of Korea but failed.

On the 22nd of August 1910, Japan annexed Korea under the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty, and Gojong lost his title of emperor but was recognised as a member of the Imperial Family of Japan.

This then was the status of Korea and her father’s position when Deokhye, Gojong’s youngest child, was born in 1912.

Princess Deokhye (Wikimedia Commons)

Although he’d previously had 4 daughters, none of them had survived their first year, so Deokhye was considered Gojong’s only daughter.

For the first 5 years of her life, Deokhye was called Agi, meaning ‘baby’, and was not formally recognised as a princess because her mother was not a queen.

The Korean royal family (L-R): Crown Prince Uimin, Emperor Sunjong (who’d succeeded Gojong), Gojong, Empress Sunjeong (Sunjong’s wife), and little Deokhye (Wikimedia Commons)

Gojong loved her very much and, seeing how intelligent she was, built the Deoksugung Kindergarten for her in 1916, which would also be attended by girls from noble families.

But, because she didn’t have an official title, Deokhye was ignored by most others and treated as if she didn’t exist.

In 1917, Gojong persuaded the Governor-General of Korea to enter Deokhye’s name into the registry of the Imperial Family, granting her legitimacy and the title of princess.

Deokhye’s popularity with the Korean people didn’t escape the attention of the Japanese authorities.

To protect his daughter, Gojong planned a secret engagement between her and the nephew of one of his court chamberlains, but the Japanese authorities discovered the plan and put a stop to it.

Then, on the 21st of January 1919, at the age of 66, Gojong died suddenly at Deoksu Palace despite not being ill.

The suddenness of his death led to rumours quickly circulating that he’d been poisoned by Japanese officials; interestingly, that was never disputed.

Her father’s death meant Deokhye was now seen as a ward of the Japanese occupation government, but her life continued as normal, and she attended school in Seoul.

In 1925, Deokhye, then 13 years old, was sent to Japan supposedly to continue her studies alongside her brothers in Tokyo, but the more obvious reason was to stop the possibility of the Korean people organising a rebellion around her.

Princess Deokhye, April 1925 (Wikimedia Commons)

Although there are few details of her life in Tokyo, she was known as a quiet, awkward young girl at the school she attended.

In 1929, Deokhye’s mother died, and she was given permission to return to Korea for her mother’s funeral but was subject to the humiliation of not being allowed to wear the proper funeral clothing.

Princess Deokhye, 1920s (Wikimedia Commons)

After Deokhye returned to Tokyo, she began to experience sleepwalking and, as her behaviour became more unpredictable, she moved to the house of her half-brother, Crown Prince Yi Un.

Crown Prince Yi Un (Wikimedia Commons)

Although the 7th son of Gojong, Yi Un became crown prince over his older brother as the latter’s mother had already died which meant he had little support at court.

But being the crown prince meant Yi Un was used as a pawn by the Japanese authorities to prevent Gojong taking any further anti-Japanese actions, and in 1907, aged only 10, Yi Un was enrolled in school in Tokyo.

As Deokhye’s condition deteriorated, she’d often forget to eat and drink, and was eventually diagnosed with precocious dementia, known today as schizophrenia.

At the time, most mental illness, including precocious dementia, was little understood.

By the following year, her condition seemed to have improved.

When she’d first been diagnosed, Deokhye had been promised in marriage to a Japanese aristocrat, but her brother, Yi Un, had protested and, because of her condition, the marriage was postponed.

However, once Deokhye showed signs of improvement, the marriage went ahead, and Yi Un was powerless to stop it.

Deokhye’s husband was Count Takeyuki of the Sō clan of Tsushima, the same Sō family that had acted as intermediaries between Japan and Korea, but their status was now no more than average nobility.

Princess Deokhye and Count Takeyuki (Wikimedia Commons)

A gentle and sensitive man, Count Takeyuki treated his new bride well, and Deokhye seemed happy in her marriage.

Unfortunately, she continued to be plagued by her mental condition, which required expensive treatment, and that placed a strain on the marriage.

Count Takeyuki and Deokhye at Tsuhishma, 1931 (Wikimedia Commons)

On the 14th of August 1932, Deokhye gave birth to a daughter, Masae (her Korean name was Jeonghye), the couple’s only child.

Sadly, Deokhye didn’t have the chance to be the mother she wanted to be for her child as her condition, again, deteriorated.

During 1933, she was admitted to a mental institution for the first time and remained there through the Second World War.

One of the conditions she’d developed was aphasia, an inability to understand or formulate language, and this must have severely impacted her relationship with Masae.

In 1941, Japan entered the Second World War, and Crown Prince Yi Un was obliged to serve in the Japanese army until Japan surrendered in 1945.

After the war, the Japanese aristocracy was abolished, which meant Count Takeyuki lost his title, political power, and any source of income.

Korea, however, was, once again, independent.

Because of Deokhye’s continuing poor mental health, Takeyuki sought permission from Crown Prince Yi Un to divorce Deokhye, which he did in 1955.

Takeyuki would eventually marry a Japanese woman, and they would have 3 children together.

Deokhye’s daughter, Masae, graduated from university and got married in 1955.

Yet, tragedy still dogged Deokhye; Masae disappeared in August 1956, and was never seen again.

It is believed she’d committed suicide because of the stress of her parent’s divorce; her suicide note had been found in the mountains.

Losing her daughter aggravated Deokhye’s condition and she continued to deteriorate.

Most likely, she remained oblivious to the fact that her home country had endured yet another war so soon after the Second World War.

After the Korean War (1950-1953), Korea split into North and South Korea; the North with the communist Soviet Russia bloc, and South with the capitalist bloc led by America.

Under the rule of President Rhee Syng-man, South Korea did, for a time, contemplate the idea of authoritarian rule, which meant the authorities believed the presence of the royal family might lead to political instability.

For this reason, Yi Un’s petitions to the South Korean government to allow him and Deokhye to return home were repeatedly opposed.

Finally, in 1961, circumstances changed, possibly because Rhee Syng-man was no longer president, and Deokhye was granted permission to return to Korea.

On the 26th of January 1962, Princess Deokhye flew home, and wept on seeing her homeland for the first time in 37 years.

Princess Deokhye’s return to Korea

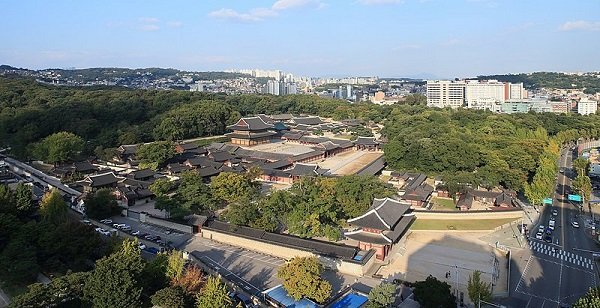

Deokhye’s childhood home, Changdeok Palace in Seoul, had been restored as a residence for the surviving members of the Korean royal family, and it is here that she spent her remaining years.

Changdeok Palace, Seoul (Wikimedia Commons)

Although Deokhye had been allowed to return home, her half-brother, Yi Un wasn’t granted permission until November 1963.

He’d suffered a stroke in 1959, and at the time of his return, was unconscious from cerebral thrombosis and was treated at a hospital in Seoul.

Crown Prince Yi Un and his wife, Yi Bangja, 1923 (Wikimedia Commons)

Along with his wife, Yi Bangja (Princess Masako of Nashimoto, Japan) and son, Prince Yi Ku, Yi Un also lived at Changdeok Palace with Deokhye, and died on the 1st of May 1970.

Although her mental condition periodically stabilised, Deokhye spent her last years in and out of various hospitals.

Princess Deokhye died on the 21st of April 1989, aged 76, and is buried at Hongneung Royal Tomb, just south of Seoul, close to where her father, Gojong and his consort, Empress Myeongseong, are buried.

Hongneung Royal Tomb (tripadvisor.de)

It’s so sad that the deck seemed stacked against Deokhye through her life, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the upheaval surrounding her in her young, formative years, especially the sudden death of her loving father, played a big part in her mental state.