Midweek Writer-Rummage: The Wild Hunt

I’d heard of the ‘Wild Hunt’ before, in relation to the goddess Diana, referred to in works of fiction and non-fiction. The images conjured just from the name alone have always fired my imagination. I didn’t think of it straightaway but at some point in the writing process, I decided I wanted to include an element of it in the story.

'The Wild Hunt' ~ Johann Wilhelm Cordes

Wild Hunt mythology stretches back to Germanic folklore, when Odin was said to lead the Wild Hunt around the time of the winter solstice, chasing wood elves.

'Åsgårdsreien' (The Ride of Asgard) ~ Peter Nicolai Arbo

But the goddess Diana has always been the classic leader of the Hunt, accompanied by her night-riders, the Furious Horde. The Horde was made up “people taken by death before their time, children snatched away at an early age, victims of a violent end”.

Unfortunately, during the time of the Inquisition, her followers were wrongly condemned as witches and suffered atrocious persecutions despite Diana the Huntress being a goddess of the hunt, not a witch. But the 1486 publication of theMalleus Maleficarum (treatise on the prosecution of witches, translated as ‘ Hammer of [the] Witches’) stated: “ It is also not omitted that certain wicked women, perverted by the devil and seduced by the illusions and phantasms of demons, believe and profess that they ride in the night hours on certain beasts with Diana, the heathen goddess, and an innumerable multitude of women, and in the silence of the dead of night do traverse great spaces of the earth.”

Britain has various versions of the Wild Hunt, dating back to the 12th century. Because these early reports were recorded by clerics, they were believed to be diabolical occurrences. An actual account of the Wild Hunt can be found in one of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the Peterborough Chronicle: “Many men both saw and heard a great number of huntsmen hunting. The huntsmen were black, huge, and hideous, and rode on black horses and on black he-goats, and their hounds were jet black, with eyes like saucers, and horrible. This was seen in the very deer park of the town of Peterborough, and in all the woods that stretch from that same town to Stamford, and in the night the monks heard them sounding and winding their horns.”

In late medieval romances, however, the participants of the Wild Hunt are portrayed as fairies. The leader of the Hunt differs, depending on the region and the story; they include Arawn, King of Annwn, the Underworld in Welsh mythology (or Gwynn ap Nudd in Arthurian legend); Woden; the Devil; King Arthur himself in Somerset – it is said that, on wild winter nights, the king and his hounds can be heard racing along an old lane near Cadbury Castle.

Herne the Hunter is also said to lead the Wild Hunt. Herne was the royal Master of the Hunt during the reign of King Richard II, from 1377-99, while he was resident at Windsor Castle.

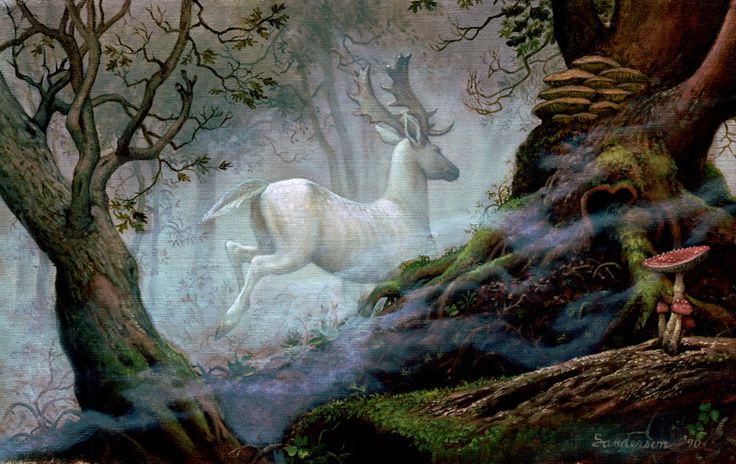

One morning, while the king and Herne were hunting in the Royal Forest, they spied a white stag in a clearing. To the surprise of all, the stag did not run. Instead, it faced the huntsmen and their hounds, and charged at Richard’s horse. Startled, the horse threw the king. Without any hesitation, Herne rushed forward, placing himself between the king and stag. The huntsman was able to kill the beast but not before he himself was severely injured by the stag’s antlers.

(Ruth Sanderson)

As Herne lay dying, a stranger on a black horse appeared. He gave his name as Urwick and said he was a wise man and that he had the power to heal Herne. With the king’s permission, Urwick affixed the stag’s antlers to Herne’s head, and carried him away, melting back into the forest.

Richard and his entourage believed they would never see Herne again. But, in time, Herne returned to Windsor. The king was overjoyed and, as reward for saving his life, Richard gave his Master of the Hunt treasures and a royal apartment. But Herne’s new wealth and royal favour only served to make his fellow huntsmen jealous. Two, in particular, started a rumour that Urwick was really a dabbler in the dark arts, and that Herne was now practising evil magic. Due to pressure from the majority of his people, Richard had no choice but to dismiss Herne despite the man insisting he was innocent of the charges.

Later the same night, Herne was discovered hanging from a large oak tree. No one knew if he’d taken his own life or if he’d been murdered. There was a fierce storm and the oak tree was struck by lightning. Come the morning, Herne’s body was gone.

From that day, Herne’s ghost would appear, every night at midnight during winter. He would ride his steed through Windsor Forest, the stag’s antlers on his head.

'Herne the Hunter' ~ George Cruikshank

As for the King’s huntsmen, without their Master of the Hunt, they lost the ability to hunt and had to face Richard’s anger – at their incompetency and the loss of Herne. Desperate to get back in the king’s favour, the huntsmen went in search of Urwick. He told them they had to make right the wrong they’d done to Herne. He told them to go to Herne’s Oak with their horses and hounds. There, they were to join with their Master, to ride forever the night skies, hunting the souls of the dead.

The hounds which accompany Herne and his hunters are called Gabriel Hounds because, in old lore, it was the Archangel Gabriel who summoned souls to judgement. In Northern England, the hounds are known as Ratchets. In Welsh mythology, the spectral hounds are called Cŵn Annwn (‘koon anoon’), the red-eared white hounds of Annwn; not surprisingly, the appearance of these hounds was a portent of doom.

(Celtic Fairy Hounds - Cwn Annwn) ~ Roger Garland