Tuesday's Tales - Remembering the War Dead

For a civilian like myself, someone who has never had to experience mortal danger, it is strange to read that, during the brutal, bloody battles of the First World War, the like of which had never been experienced before, thoughts turned to ways of honouring the dead. Not just of honouring one’s own dead, but those of the ‘enemy’ as well – to have men who, when alive, fought ferociously against one another lie, in death, closely beside each other …

The idea of ‘The Unknown Warrior’ has passed into history, and it has become an expected thing, that by focussing on one ‘unknown’, we honour all those who have given their lives in war. And yet, 100 years ago, the idea was so ‘new’, that no response was forthcoming when a written proposal was sent to Lord Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force from 1915 to the end of the war.

The grave of ‘The Unknown Warrior’, which dates from November 1920, is at the west end of the Nave of Westminster Abbey.

The idea for such a grave came to the Reverend David Railton, an Army chaplain serving on the Western Front in 1916. He came across a simple cross in a garden at Armentières, on it an inscription: “An Unknown British Soldier”. He later wrote: “I thought and thought and wrestled in thought. What can I do to ease the pain of father, mother, brother, sister, sweetheart, wife and friend?”

Reverend David Railton

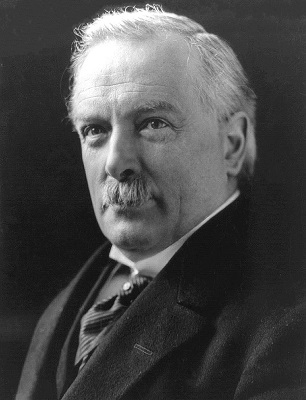

He was the one who had earlier written to Lord Haig about his idea. Having gotten no response, he wrote, in August 1920, to the Dean of Westminster Abbey, Herbert Ryle, with the idea of a place for the body of an unknown warrior, a single grave to represent all the war dead. The Dean was very taken with the idea, as was Prime Minister David Lloyd George. However, there were doubters, and these included King George V. As that was the same year the Cenotaph was to be unveiled, the king feared the tomb might prove one remembrance event too many. But Lloyd George managed to win the monarch over.

Herbert Ryle

David Lloyd George

King George V

The selection process involved choosing one of four bodies of unknown British servicemen – they were known to be British only by their boots and buttons; there was no other way of identifying them – they were exhumed from the battlefields of Arras, Aisne, the Somme and Ypres. Each body was placed in an old sack and plain coffin, taken to the chapel at St. Pol on the night of 7 November 1920, and each draped with a Union flag. The Commander of the British Army in France and Flanders, Brigadier General LJ Wyatt, entered the chapel and selected one, having no idea which area the bodies had come from.

The next morning, the Chaplains of the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church and Non-Conformist churches held a service in the chapel. The selected coffin was then placed inside another, made of oak from the garden of Hampton Court Palace. It was then covered with the flag that David Railton had used as an altar cloth during the war – it now hangs in St George’s Chapel, and is known as the Ypres or Padre’s Flag. A 16th century crusader’s sword from the Tower of London collection, bequeathed by the king, was placed in the coffin. The coffin plate bore the inscription: “A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country”.

The body travelled by carriage to Boulogne, and then across the Channel on board HMS Verdun; the ship’s bell was presented to the Abbey and now hangs near the grave. At Dover, the body was taken to London in South-East Railways Passenger Luggage Van 132, the same railway carriage that had borne the body of Edith Cavell.

Passenger luggage van (on left) - Kent and East Sussex Railway

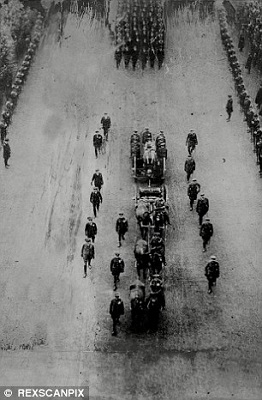

After spending the night in Victoria Station, with a guard of four, the next morning, 11 November, the coffin was placed on a gun carriage drawn by the 'Old Blacks' to begin its journey through the streets, lined with crowds the like of which the capital had never seen before. It stopped first at Whitehall where King George unveiled the Cenotaph. He then placed his wreath of red roses and bay leaves on the coffin; his card read:

“In proud memory of those Warriors who died unknown in the Great War. Unknown, and yet well-known; as dying, and behold they live. George R.I. November 11th 1920”.

The carriage then made its way to the north door of Westminster Abbey.

By the Cenotaph

During the service, as the coffin was lowered into the grave, the King dropped a handful of French earth onto the coffin. After the service, the grave was covered by a silk funeral pall, over which was laid the Padre’s flag. As servicemen kept watch, mourners filed past; it was estimated that one million people filed past the grave in five days.

On 18 November, the grave was filled with earth from the battlefields, carried in six barrels from France. It was covered with a temporary stone with a gilded inscription:

“A British Warrior Who Fell In The Great War 1914-1918 For King And Country.

Greater Love Hath No Man Than This”.

On 11th November 1921, the black marble stone that now covers it was unveiled at a special service. The inscription was composed by the Dean, Herbert Ryle:

BENEATH THIS STONE RESTS THE BODY

OF A BRITISH WARRIOR

UNKNOWN BY NAME OR RANK

BROUGHT FROM FRANCE TO LIE AMONG

THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS OF THE LAND

AND BURIED HERE ON ARMISTICE DAY

11 NOV: 1920, IN THE PRESENCE OF

HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE V

HIS MINISTERS OF STATE

THE CHIEFS OF HIS FORCES

AND A VAST CONCOURSE OF THE NATION

THUS ARE COMMEMORATED THE MANY

MULTITUDES WHO DURING THE GREAT

WAR OF 1914-1918 GAVE THE MOST THAT

MAN CAN GIVE LIFE ITSELF

FOR GOD

FOR KING AND COUNTRY

FOR LOVED ONES HOME AND EMPIRE

FOR THE SACRED CAUSE OF JUSTICE AND

THE FREEDOM OF THE WORLD

THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE

HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD

HIS HOUSE

Around the main inscription are four texts:

At the top: THE LORD KNOWETH THEM THAT ARE HIS

At the sides: GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS

UNKNOWN AND YET WELL KNOWN, DYING AND BEHOLD WE LIVE

At the base: IN CHRIST SHALL ALL BE MADE ALIVE

11 November 2009 - Getty Images

Going back in time to the beginning of the war … 23 August 1914, the Battle of Mons, the first major battle of the British Expeditionary Force. The casualties on both sides – about 1,600 British, and between 3,000-5,000 Germans – were buried in makeshift graves in fields, churchyards and cemeteries around Mons.

In 1916, a German officer, Captain Roemer, asked a Belgian landowner, Jean Houzeau de Lahie, for land, just south-east of Mons, to bury the dead, not just German, but British also. Monsieur de Lahie refused to sell; instead he agreed that it could be used as a burial site on one condition – the graves of both nations were to be treated with dignity and respect.

The German army began exhuming the bodies for re-interment in the St. Symphorien Military Cemetery, which was inaugurated on 6 September 1917. It contained the graves of 229 Commonwealth servicemen, and 284 German soldiers. It is overlooked by a ‘ granite obelisk some seven metres high’, commemorating the dead from both sides in the Battle of Mons, and a Commonwealth Cross of Sacrifice. To resemble a German forest cemetery, trees and shrubs were planted; flowers also were planted to resemble an English garden.

St. Symphorien contains the grave of the first Iron Cross recipient of the War. It also shelters the remains of the two British servicemen traditionally believed to be the first and last British soldiers killed in action in the War – Private John Parr, the 17-year-old son of a milkman from north London, killed in August 1914; and Private George Lawrence Price, a 40-year-old from Yorkshire, killed hours before the Armistice.

The cemetery passed into the care of the Imperial War Graves Commission, now called the Commonwealth War Graves Commission at the end of the war in 1918; and now contains the graves of 334 Commonwealth and 280 German servicemen of the First World War.

The cemetery sounds a very peaceful, elegant place … it’s been described like “ entering an enchanted forest … [The] headstones are gathered in small groups in woodland glades. The silence … is broken only by birdsong …” ~ Sophie Raworth, reporter.

(Jean-Pol Grandmont)