The Sunday Section: Snippets of ... Knights and Crusades

While sorting out last week’s blog post, I realised I had a whole lot more about knights (mainly their armour and weapons), and the Crusades. Instead of trying to cram everything into the one post, I decided to do a separate one. Like I’ve said before, this information isn’t all there is to know; I only made notes of what was of personal interest to me.

(by Graham Turner)

KNIGHTS:

ARMOUR: The main body armour of early knights was made of mail, consisting of many small, linked iron rings:

12th century – more mail was added with longer sleeves, and mail leggings. A padded garment – called aketon, or arming coat, or gambeson, or doublet – was worn below the mail to absorb blows.

14th century – steel plates were added to protect the limbs, and the body was further protected with a coat-of-plates made of pieces of iron riveted to a cloth covering.

By 1400, full suits of armour were being worn, which weighed about 44-55lb. The weight was spread over the body so that a fit man could run, lie down or mount a horse unaided; but the wearer became very hot very quickly.

Plate armour afforded better protection than mail because it was solid and did not flex when struck by a weapon.

To make mail in the 15th century – pliers were used to join the links, with garments being shaped by increasing or reducing the number of links in each row, much like a knitting pattern.

A man in armour could do anything a man can do when not wearing it – the secret lay in the way armourers made the plates so that they could move with each other and with the wearer.

Some plates were attached with a rivet, which allowed the 2 parts to pivot at that point.

The sliding rivet, one part of which was not set in a round hole but in a slot, so the 2 plates could move in and out.

'Leathers' - internal leather connecting straps, which also allowed similar movement as the sliding rivet.

After donning the doublet over underclothes (important to prevent chaffing!), the knight would be armed from the feet upwards, starting with:

Sabatons – foot armour; with spurs buckled over it.

Mail

Cuisse and Poleyn – leg armour; cuisse being thigh armour, and poleyn for the knee. The back of the thigh was usually left unprotected. Holes at the top of the cuisse allowed it to be laced to the wearer's torso.

Back and Breast plates

Pauldron and Vambrace – arm armour. By the late 16th century, the pauldron (shoulder defence) was made of several plates connected by sliding rivets and internal leathers, to allow them to move over one another. The pauldron was connected to the vambrace on the upper arm by a turner which allowed the arm to twist outwards; leathers connected the upper arm, elbow and lower arm.

Gauntlets – fitted with a leather glove inside to allow the knight to better grip his weapons.

The helmet was lined inside, not only for comfort, but also to cushion blows.

Sword belt had straps, which allowed it to be held against the body, front and back, so the scabbard could be held at a convenient angle.

WEAPONS:

Sword – the knight’s weapon of choice. By the 14th century, the central groove or fuller of a sword was replaced by a stiffer one with a diamond-shaped profile, which assisted the thrust – the acute point could burst apart the links of a piece of mail. As plate armour became more common, so did pointed swords increase in popularity – better for thrusting through the gaps between plates. The pommel is more than simply decorative; it is basically a counterweight to help give the weapon balance.

Using the high guard as the starting point gives the defendant the benefit of gravity in his attacks; called ‘La Posta di Falconé’ (Guard of the Hawk) – holding the sword upright at an angle of 45° instead of at a low guard provides the user the ability to deliver a natural, fast and extremely powerful cut.

The scabbard can also be used as a weapon; once the sword is drawn, the scabbard can be used to block an attack, or beat an opponent. Most are made of leather.

As a little aside – according to films, when a sword is drawn it makes a metallic sound; this is inaccurate, for if a scabbard has metal in it, it would dull the blade.

Dagger – apart from stabbing at the opponent or cutting the throat, it could also pierce mail.

Mace – could crush a skull without spilling a drop of blood. It was popular because it was cheap, and effective against armour; was considered the weapon of the poor. A flanged mace has ridges sticking out from the head to concentrate the force of the blow.

Flail – made of one or more spiked metal balls attached to a handle by a chain or hinge. The ‘morning star’ has one large metal ball with no hinge. The flail was more powerful than the mace because the metal ball was swung in circles to gain momentum before it was brought down to crash on the enemy. But it took time and patience to master, to maintain the correct velocity, and for the user not to injure himself.

Lance – the impact of 2 riders closing at about 60mph made the pointed lance a lethal weapon; it could punch through armour.

(by Igor Dzis)

CRUSADE:

The word comes from the Medieval Latin, ‘cruciata’, and the Latin, ‘crux’, and referred to the cloth emblem of the cross worn by the participants, those who were willing to ‘take up the cross’. Ironic that while Jesus referred to taking up the burden of what was a pacifist philosophy, the crusaders were using it in the name of war.

The etymology of ‘Jerusalem’ is from the Hebrew ‘Yerushalayim’, which is a derivation of a much older name of a city that existed there in the Bronze Age; the name denotes ‘completeness’ and alludes to ‘peace’ – yet more irony. In Arabic, the most common name is ‘al-Quds’, which refers to a city that is ‘holy’.

(Jerusalem 1299) ~ Claude Jacquand

The name ‘Saracen’ came from the Greeks and Romans, who applied it to the nomads of the Syrian and Arabian deserts, but it came to specifically represent ‘Middle Eastern Muslim’ during the Crusades.

Hospitalier – named for the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, founded in 1070AD as a means of administering to the sick in Jerusalem. When the Crusades began, the order also became a military operation. Their name was derived from their use of hospitals.

A bitter rivalry existed between Hospitaliers and the Templars, not only in terms of their order and uniforms – the Hospitaliers’ was a white cross on a black background, while the Templars wore a red cross on a white background; but also in terms of their function. The Hospitaliers were established to protect and minister to the medical and spiritual needs of pilgrims who came to Jerusalem; the Templars were established purely as a military presence.

The Hospitaliers would last into the 18th century, but with little direct connection to the original. On the other hand, the Templars, who in their 200-year history, had grown rich and strong, enough to cause concern in Europe, were imprisoned in 1307, and their leaders executed for heresy, blasphemy and sorcery, even though the ‘confessions’ had all been obtained under torture. The order was permanently dissolved in 1312.

The era of the Crusades saw the invention of the crossbow and the compass, and led to the West being introduced to the printing press, and gunpowder; to pepper, ginger, cloves, rice, sesame, oranges, lemons, melons, dates, peaches and sugar; silk, velvet and the ability to dye clothes; perfumes and powders.

The Muslim method of hardening swords was the ‘Damascene process’ – this was done by thrusting a superheated blade into the body of a slave, and then into water. The Crusaders found that swords made of Damascus steel were more resilient and harder than European ones. When the Europeans eventually learned of this technique, they discovered a less brutal approach; the same hardening process was accomplished by thrusting the red-hot sword into a mass of animal skins soaking in water. It is the nitrogen given off by the skins in the water that produces a chemical reaction in the steel, causing it to harden.

In the Middle East, tombs were the preferred method of burial; this led to the invention of catacombs. The earliest subterranean tomb is at ‘Me-arat ha-Machpela’ or ‘Cave of the Patriarchs’, where Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Leah are supposedly buried.

This piece of information was from a recent programme, ‘The Crusades’. I always thought that King Richard earned his moniker, ‘Lionheart’ from the fighting he’d done during the Third Crusade. He’d been successful in the fighting he and his men had done on the way to Jerusalem, but had never actually been in the Holy City. When he was within 12 miles of the city, he ordered a withdrawal because his fragile supply lines were threatened by bad weather. For his men, who viewed the Crusade as the means by which to make a pilgrimage to the holiest of cities, this was akin to a betrayal of their faith and trust, and many returned home.

King Richard

Richard was in the awkward position of, not only being the leader of the Crusades, but also an Angevin king; he had to decide whether to fight for Jerusalem, or to return home and secure his kingdom. Because he lacked resolve and could not make a firm decision, he lost control of the crusade when his men made the decision for him and marched on the Holy City.

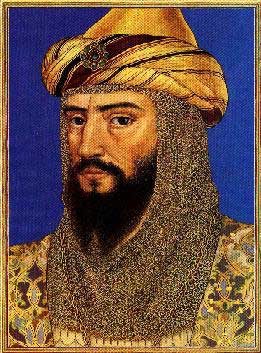

Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, better known in the West as Saladin

Ironically, the leader of the Saracens, Saladin, was facing problems with his own men. For various reasons, they were threatening mutiny. After an agonising night, Saladin made the startling decision to abandon the city. Mere hours from the city, Richard made the equally startling decision not to attack. Apparently, he said he was ‘unwilling to lead the crusade on such a rash venture, because it would end in terrible disgrace for which he would be forever blamed, shamed and less loved.’ After all the campaigning, all the money raised, and the lives lost, it seems as if, when it came to the crunch, Richard was worried about his reputation.

So the Third Crusade ended with neither side scoring a victory. Richard left the Holy Land without ever having set foot in Jerusalem. He returned to Europe where he successfully held onto his kingdom for the next decade until killed by a crossbow bolt. Not quite the legendary crusader knight …