The Sunday Section: Book Review - 'Storm of Steel'

This is the first WW1 memoir I’ve read by a German, Ernst Jünger. He wrote this, his first book, after the war, and it was published in 1920.

According to the Telegraph’s Charles Moore: “Undoubtedly the most powerful memoir of any war I have ever read … Storm of Steel combines the most astonishing literary gifts with absorption with war in every detail. It has German loyalties and a German sensibility, but not a trace of propaganda. It is particular, yet universal … What Jünger saw and recorded was, to use his own word, ‘primordial’. It takes great art to convey that appalling simplicity.”

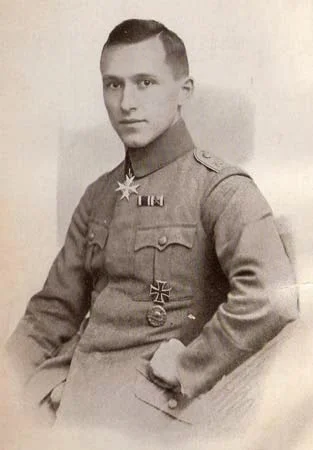

The translation by Michael Hofmann is very good, in my opinion; nothing jarred me out of the narrative, which flowed smoothly. It’s a straightforward account of Jünger’s experiences in the war. It begins, without any deep and meaningful introduction, with his arrival in France in 1914, aged 19, and simply states, “The train stopped at Bazancourt, a small town in Champagne, and we got out.” The book ends in 1918 when he’s back in Germany, too wounded to continue in the war, a decorated lieutenant and the youngest-ever recipient of the pour le Merite.

There is no mention of the politics of the war, or the reasons for it; there is no attempt at analysis, or laying of blame. Jünger is honest in stating that the war was one of the greatest experiences of his life, and he makes no apologies for that. There is no hatred as such for the British and French soldiers, they were simply ‘the enemy’ …

‘Throughout the war, it was always my endeavour to view my opponent without animus, and to form an opinion of him as man on the basis of the courage he showed. I would always try and seek him out in combat and kill him, and I expected nothing else from him. But never did I entertain mean thoughts of him. When prisoners fell into my hands, later on, I felt responsible for their safety, and would always do everything in my power for them.’

Because there is no self-examination on Jünger’s part, it is pretty much impossible to fathom what his rationale was; all you’re left with is the sense of someone doing the job he was trained to, and sent to, do. His economical use of the language in describing his experiences does nothing to diminish the awfulness of war. The way he describes, for example, an artillery barrage, and its effects, reads like special effects being described in a screenplay for a film; it isn’t difficult to imagine being there …

‘Twenty yards behind us, clumps of earth whirled up out of a white cloud and smacked into the boughs. The crash echoed through the woods. Stricken eyes looked at each other, bodies pressed themselves into the ground with a humbling sensation of powerlessness to do anything else. Explosion followed explosion. Choking gases drifted through the undergrowth, smoke obscured the treetops, trees and branches came crashing to the ground, screams. We leaped up and ran blindly, chased by lightnings and crushing air pressure, from tree to tree, looking for cover, skirting around giant tree trunks like frightened game. A dugout where many men had taken shelter, and which I too was running towards, took a direct hit that ripped up the planking and sent heavy timbers spinning through the air.’

There is no mention of family, except when he learns that his beloved brother, Fritz, has been wounded ...

'Out of the blue, Sandvoss asked me if I'd heard about my brother. The reader may imagine my consternation when I learned that he'd taken part in the night attack, and had been reported missing. He was the dearest to my heart, a feeling of appalling, irreplaceable loss opened up in front of me.'

Jünger’s desperate endeavours to get his brother to safety makes for emotional reading.

Interestingly, the book also includes the same scene, retold, from Fritz’s point of view ...

‘Suddenly, bespattered with mud from his boots to his helmet, a young officer burst in. It was my brother, Ernst, who at regimental HQ the day before had been feared dead. We greeted one another and smiled, a little stiffly, with the emotion. He looked about him and then looked at me with concern. His eyes were filled with tears. We might both be members of the same regiment, true, but even then this reunion on the battlefield had something rare and wonderful about it, and the recollection of it has remained precious to me.'

Recovering from the wounds he suffered, which eventually saw him sent home, Jünger counted the number of wounds he’d received over the years:

… ‘Leaving out trifles such as ricochets and grazes, I was hit at least fourteen times, these being five bullets, two shell splinters, one shrapnel ball, four hand-grenade splinters and two bullet splinters, which, with entry and exit wounds, left me an even twenty scars. In the course of this war, where so much of the firing was done blindly into empty space, I still managed to get myself targeted no fewer than eleven times …’

Personally, I don’t believe this book should be disregarded simply because the author was German. It gives a very honest account of what it was like to fight in a war like the First World War, and what that experience does to a person. And it is that honesty which makes this book one that should be mandatory reading for anyone interested in war and its effects on the soldier.